Parameterizing Specs¶

Model Constants¶

In the last chapter, we made a complete specification of the duplicate checker, adding a property to our implementation. By using initial states, we can check all 4-digit lists of single digits. If we wanted to be more thorough, we could check a wider range of inputs, for example S == 1..100. By my estimate, this would kick the number of found states from 70,000 to over 500,000,000. That would take a lot more time to check! If we were writing this as a “real” spec, we’d want to do most of our writing with a smaller value of S, like 1..10, so we can get faster feedback from the model checker. It’s only when we’ve shaken out the obvious issues that we’d switch a large value of S, like 1..100.

This means we don’t want S to be a hardcoded value in the spec. It should instead be something we can dynamically pick per model run. Think of how, in a programming language, you have command line flags for passing in arguments. In TLA+, values that can be configured per model run are called “Constants”.1 Let’s make S a constant:

---- MODULE duplicates ----

EXTENDS Integers, Sequences, TLC

-

-S == 1..10

+CONSTANT S

(*--algorithm dup

-variable

- seq \in S \X S \X S \X S;

+ variable seq \in S \X S \X S \X S;

index = 1;

seen = {};

is_unique = TRUE;

@@ -18,7 +16,7 @@

IsUnique(s) ==

\A i, j \in 1..Len(s):

- i # j => s[i] # s[j]

+ i # j => seq[i] # seq[j]

IsCorrect == pc = "Done" => is_unique = IsUnique(seq)

end define;

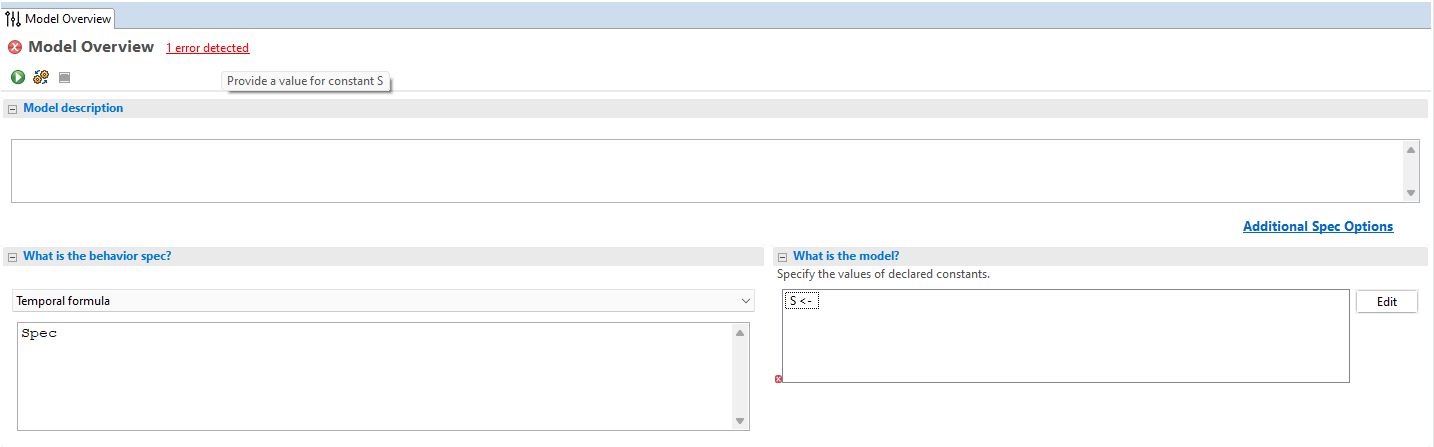

You can put several constants on the same line; when we make the length configurable (in the next chapter), we’ll write CONSTANT S, Length. If we now try to run our spec, the toolbox will say that we haven’t defined the constant S:

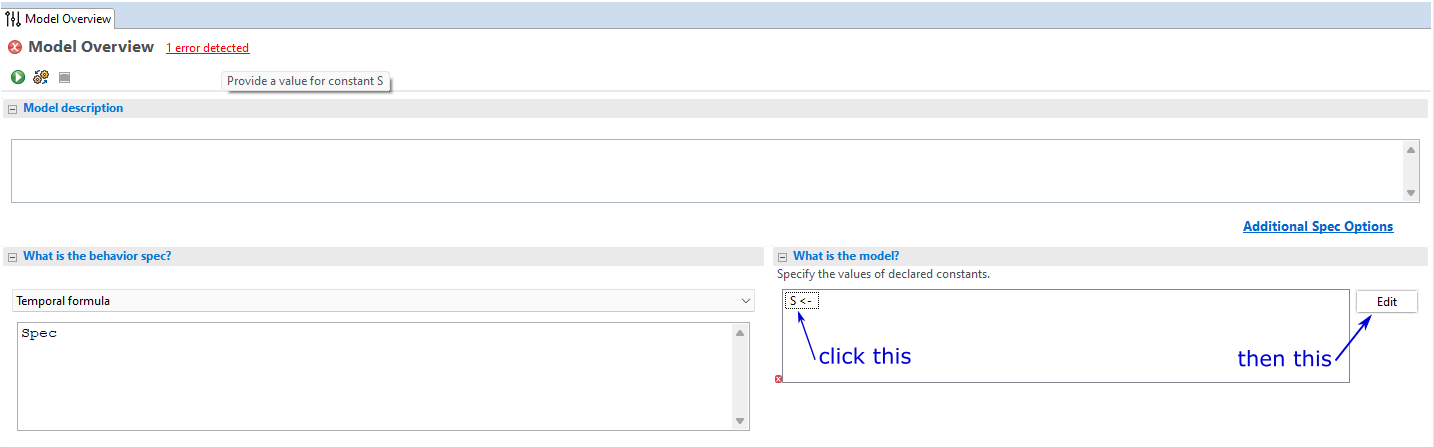

We do that over here:

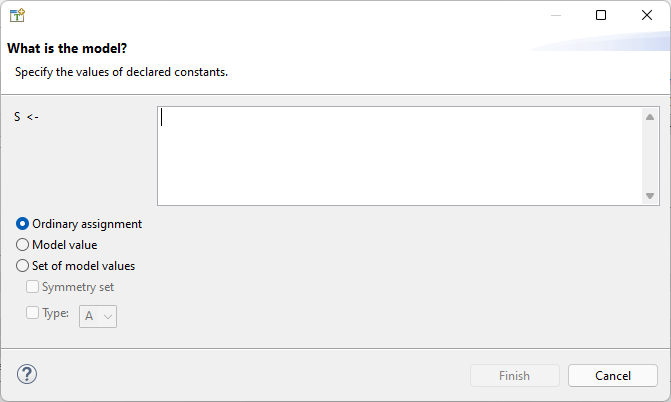

Which opens this box:

There are three options for constants: ordinary assignments, model values, and sets of model values. We’ll talk about the other two later, for now let’s just look at ordinary assignments. This lets you assign any valid TLA+ expression to the constant. Since showing screenshots of every single assignment is annoying, I’ll write S <- 1..10 to mean “we do an ordinary assignment of 1..10 to S.” Now we can make separate models with a small S for iterative development and one with a large S for final testing.

Note

It’s good practice to use constants in your TLA+ specs. To keep the examples simple, though, I’ll hardcode more values than I normally would.

Preventing Nonsense Constants¶

Not all values of S are meaningful for our spec. For example, what if we do S <- {}? Then there’s no possible values for seq, so there’s no possible duplicates, so the entire model is pointless. Or what about S <- {1, 2}? While there are now possible values of seq, they will always contain duplicates, so running the spec isn’t particularly interesting.

We can rule these pathological values out with the ASSUME keyword. ASSUME expressions are checks to make sure we put in correct constants.

---- MODULE duplicates ----

-EXTENDS Integers, Sequences, TLC

+EXTENDS Integers, Sequences, TLC, FiniteSets

CONSTANT S

+ASSUME Cardinality(S) >= 4

(*--algorithm dup

variable seq \in S \X S \X S \X S;

The expression inside an ASSUME can depend on operators and constants, but not variables. The ASSUME is checked before the model run even starts. If we try running the spec with S <- {1}, we get an error:

Error: Assumption %line% is false.

If you have a spec with constants, you should put constraining assumptions on them. In addition to preventing errors, they also help readers of the spec understand what the constants are supposed to be.

Model Values¶

That takes care of ordinary assignments, what about “model values”? Model values are a special type of value in TLA+. A model value has no operations and can only be tested for equality, and is only equal to itself. IE

\* Given

X <- [model value]

Y <- [model value]

\* Then

X = X

X # Y

X # 1

X # "a"

X # <<1, Y>>

Why would you want this? Because in TLC, comparing incompatible types produces an error. Say you want to represent a nullable value, like last_access_time. You can’t write IF last_access_time = "null" because if the variable is currently non-null, then you’re comparing a string to an integer, which is an error. If you use a sentinel value, like IF last_access_time = -1, then you’re risking logic errors if you accidentally use it in any other numerical context.

What you can do instead is define a new constant, like NULL or NotYetAccessed, and set it to a model value. Then you can do IF last_access_time = NULL, which will be false if the value is already a number. Similarly, you can add them to sets that already have a elements. Model values are incredibly useful as sentinel and placeholder values in organizing larger specs.

Note

Once you have a model value, you can use it in ordinary assignments. For example:

CONSTANT X, Set

X <- [model value]

Set <- {1, 2, X}

Sets of Model Values¶

We can also assign constants to sets of model values. Put it in as a normal set, but without quotes.

S <- [model value] {s1, s2, s3, s4, s5}

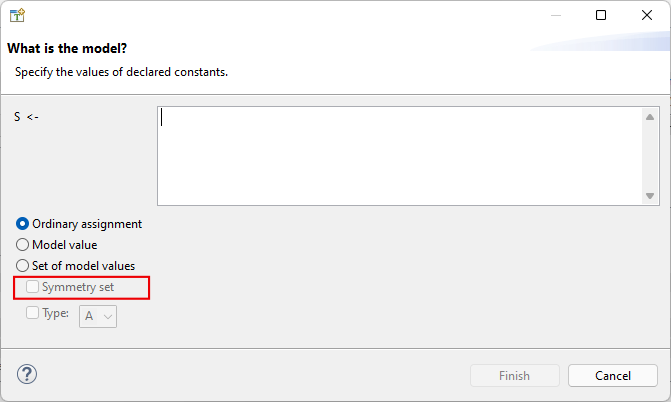

Sets of model values will become extremely useful when we start modeling concurrency, but there’s still one cool trick we can do with them right now. If you run the model with that value of S, you will get 4,375 states total— the same as if you did S <- 1..5. But notice this other option below the “set of model values” bar:

“Symmetry set” is a special TLC optimization. By making S a symmetry set, the number of states drops to only 715. Symmetry sets are a very powerful optimization technique!

To illustrate what’s going on, let’s look at four possible values for seq:

(1) <<s1, s2, s3>>

(2) <<s2, s1, s3>>

(3) <<s1, s2, s2>>

(4) <<s2, s3, s3>>

Normally we’d think of these as four separate initial states. But is that necessarily true? The only difference between (1) and (2) is that we swapped every s1 with s2. Similarly, the only difference between (3) and (4) is that in (4) we replaced every s1 with s2 and every s2 with s3. So we can tell TLC to treat these “symmetric” values as identical.

Notice this only works because we’re working with model values, which only support equality checks. If we instead had <<1, 2, 2>> and <<2, 3, 3>> the results would not be symmetric, as they’d give different results for s[1] + s[2].

Warning

Symmetry sets don’t always make the spec run faster. TLC has some overhead in figuring out all the symmetries; with very large sets, that can take longer than actually checking the model. On my computer, checking duplicates with an 8-element symmetry set takes two minutes longer than checking it with a regular model set.

Other Uses for Constants¶

You can also use constants to control the flow of your spec. When working on complicated specs, I sometimes like to make a DEBUG constant:

CONSTANT DEBUG

ASSUME DEBUG \in BOOLEAN

\* ...

macro print_if_debug(str) begin

if DEBUG then

print str;

end if;

Another thing you can do is restrict multiple starting states with DEBUG:

Inputs ==

IF DEBUG

THEN {<<1, 2, 3, 4>>}

ELSE S \X S \X S \X S

Don’t be afraid to make helper constants!

Summary¶

Constants let you use different values of something for different models.

Constants can be assigned ordinary TLA+ expressions, or model values or sets of model values.

ASSUME checks that you assign meaningful values to your constants.

Model values compare equal to themselves and nothing else. They are useful as sentinel values.

Sets of model values can be made into symmetry sets, which (usually) speeds up model checking.

- 1

This is different from how we use constant in programming languages, as well as other specification languages. AFAICT it’s an idiosyncrasy of TLA+. Constants as in “values that never change” are just 0-arity operators.